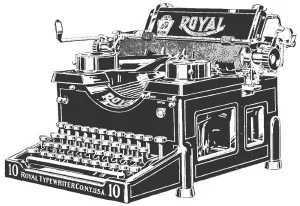

Last year, in a small village in southern England, I stumbled upon a Royal No. 10 typewriter, which was quite fascinating. My initial encounter with mechanical typewriters was when I began learning English. Back then, larger stationery stores sold standard keyboard sheets, printed on stiff paper with a QWERTY layout, for aspiring typists to practice on their desks, as genuine typewriters were quite expensive. Typing was a skill that required diligent training. Bookstores sold specialized typing tutorials to teach basic finger positions and improve typing speed, focusing on combinations like “er” and “ist,” or less common keys like “q,” “p,” and “z.” Nowadays, with the widespread use of computer keyboards, it’s hard to appreciate the difficulty of hitting those keys with the little fingers without applying the right amount of force and finesse.

Typewriters experienced significant development as office equipment after the Industrial Revolution, gradually becoming standardized around the early 20th century, with products from various manufacturers becoming increasingly uniform in structure and appearance. During World War II, typewriters were an absolute staple in offices. In “Schindler’s List,” there’s a scene where rows of desks are set up on a train platform, each with a typewriter, behind which stand queues of Jewish people, their destinies being typed out by clattering typists, turning vivid lives into cold, mechanized characters—one by one—the terrifying aspect of archives. Another typewriter-related story was featured in the “Obituary” column of The Economist magazine, published on September 18, 2008. It began like this:

Anyone who has ever used a mechanical typewriter knows that it was more than just a machine. – Unfortunately, I used the word “ever” because the typewriter is now a thing of the past. When we lifted that bulky contraption out of its case and placed it on the desk, it seemed to exude an air of anticipation, like a grand piano with its lid just lifted at a concert. The white-keyboarded, metal-rimmed keys of the old typewriter beckoned to users, inviting them to pound away, playing a concerto on the keyboard, while the silver typebars rose and fell, sometimes clacking, sometimes hissing. Such sounds once filled offices around the world and permeated the life of Martin Tytell.

Mr. Martin Tytell had a passion for typewriters from a young age, and due to his special skills, he was awarded a medal after World War II in recognition of his contributions. Indeed, excellence shines through in every field.

As for why the common keyboard layout is as it is now, there’s a somewhat plausible explanation that it’s designed to evenly distribute commonly used letters to prevent type bars from jamming together when struck too quickly. However, another explanation is a bit less reliable. It’s said that during the period of widespread popularity of typewriters in the early 20th century, manufacturers placed the word “TYPEWRITER” across the top row of letters to make it easier for less-skilled salesmen to demonstrate the machine and sell more units. Over time, the keyboard layout became standardized. But who knows which version is true? The truth often lies in the most unreliable corners.

Keyboards for other European languages differ from English keyboards. For example, French keyboards have special accents for the French language. There are also differences between British English and American English keyboards. Of course, the most common one is the American keyboard layout, which is perhaps a reflection of a nation’s soft power.

Mark Twain was an early adopter of the typewriter; his “Adventures of Tom Sawyer” was completed on a typewriter. Nietzsche also used a typewriter for his work due to his loss of eyesight. Later, there was Hemingway. Even today, Frederick Forsyth, the author of “The Day of the Jackal,” still insists on using a typewriter. His stubbornness has some merit; Mr. Forsyth believes that unlike computers, especially those connected to the internet, mechanical typewriters won’t leak the author’s secrets or suddenly go mad and destroy the author’s work.

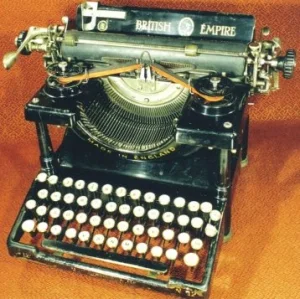

Mechanical typewriters began to decline in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and what remains in offices today are likely those electronic typewriters used for filling out forms. Mechanical typewriters, like the “Imperial” typewriter brand in the photo below, are now part of history.